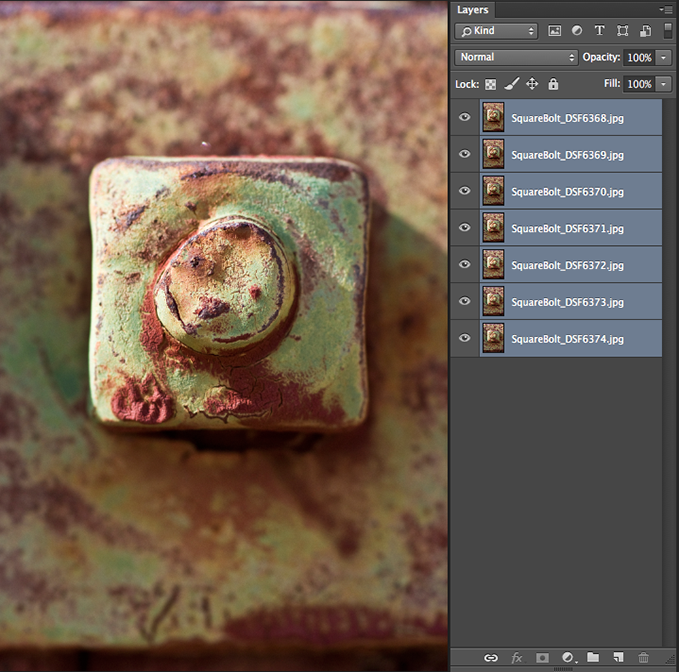

However, if I'm shooting a spider at 5x magnification on my 65mm macro lens, I will get only the two front eyes in focus and the rest is completely blurred. "Shooting at wide apertures such as f/2.8 avoids diffraction and allows me to let more light in, so I can use shorter exposures. "That's correct, but that's also going to cause diffraction, where light disperses and image sharpness is reduced, and your exposures are much longer. "Most people think that by using very small apertures you'll get more of the subject in focus," he says. He typically uses a Canon EOS 6D (now succeeded by the Canon EOS 6D Mark II) paired with a Canon MP-E 65mm f/2.8 1-5x Macro or Canon EF 100mm f/2.8L Macro IS USM lens, for their wide apertures and magnification factor. He has refined his focus stacking technique to overcome extremely narrow depth of field while shooting small subjects at high magnification. Matt Doogue began photographing insects and arachnids seven years ago. It's a great way to transcend a lens's natural limits and create images that are extraordinarily sharp and detailed throughout.īut how exactly do you take and blend focus-stacked images successfully? How does the technique differ when shooting landscapes rather than macro, what is the best kit to use, and how do you turn a succession of shots into one detailed image? Here, Canon Ambassador and nature photojournalist Christian Ziegler, macro specialist Matt Doogue and landscape and travel photographer David Clapp share how they use focus stacking to create detail-rich shots. Those images are then blended together, or 'stacked', in post-production to produce a single image that has greater depth of field, with the subject in focus throughout the frame. To create focus-stacked images, you start by bracketing a number of images of the same subject with slightly different parts of that subject in focus. Simply closing down to a small aperture may not give enough sharpness throughout the frame, particularly when shooting macro. Whether you're shooting macro images of tiny insects or a wide expanse of landscape, sometimes you crave a greater depth of field than one shot with one lens can provide.

It's arguably the biggest problem in macro photography: you get close to your subject and typically select a wide aperture to capture as much light as possible, but as a result the depth of field becomes very narrow, leaving much of your image out of focus.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)